Inside the vast, bustling network of the human brain, harmony is everything. For billions of neurons to communicate effectively, there must be a delicate balance between the signals that scream “go” and the signals that whisper “stop.” In a healthy mind, this symphony is conducted by a specialized group of neurons known as parvalbumin-positive cells. These are the brain’s rapid-braking system, the master regulators that keep neural activity in equilibrium and ensure the entire organ pulse to a steady, rhythmic beat. When these cells are functioning correctly, they reduce overactivity and make sure the brain’s electrical landscape remains stable. Scientists often describe them with a poetic simplicity: they are the cells that “make the brain sound right.”

However, when this rhythm is broken, the consequences are profound. When parvalbumin cells malfunction or begin to dwindle in number, the brain’s equilibrium is shattered. Without its rapid-braking system, the mind can fall into a state of chaotic overactivity. Previous research has suggested that these damaged or missing cells may be a significant contributor to devastating neurological conditions, including schizophrenia and epilepsy. For years, the scientific community has searched for a way to restore these specific conductors to the neural orchestra, but the path to creating them has been notoriously difficult, until a team of researchers at Lund University in Sweden discovered a way to rewrite the very identity of the brain’s supporting cast.

The Quiet Architects of Change

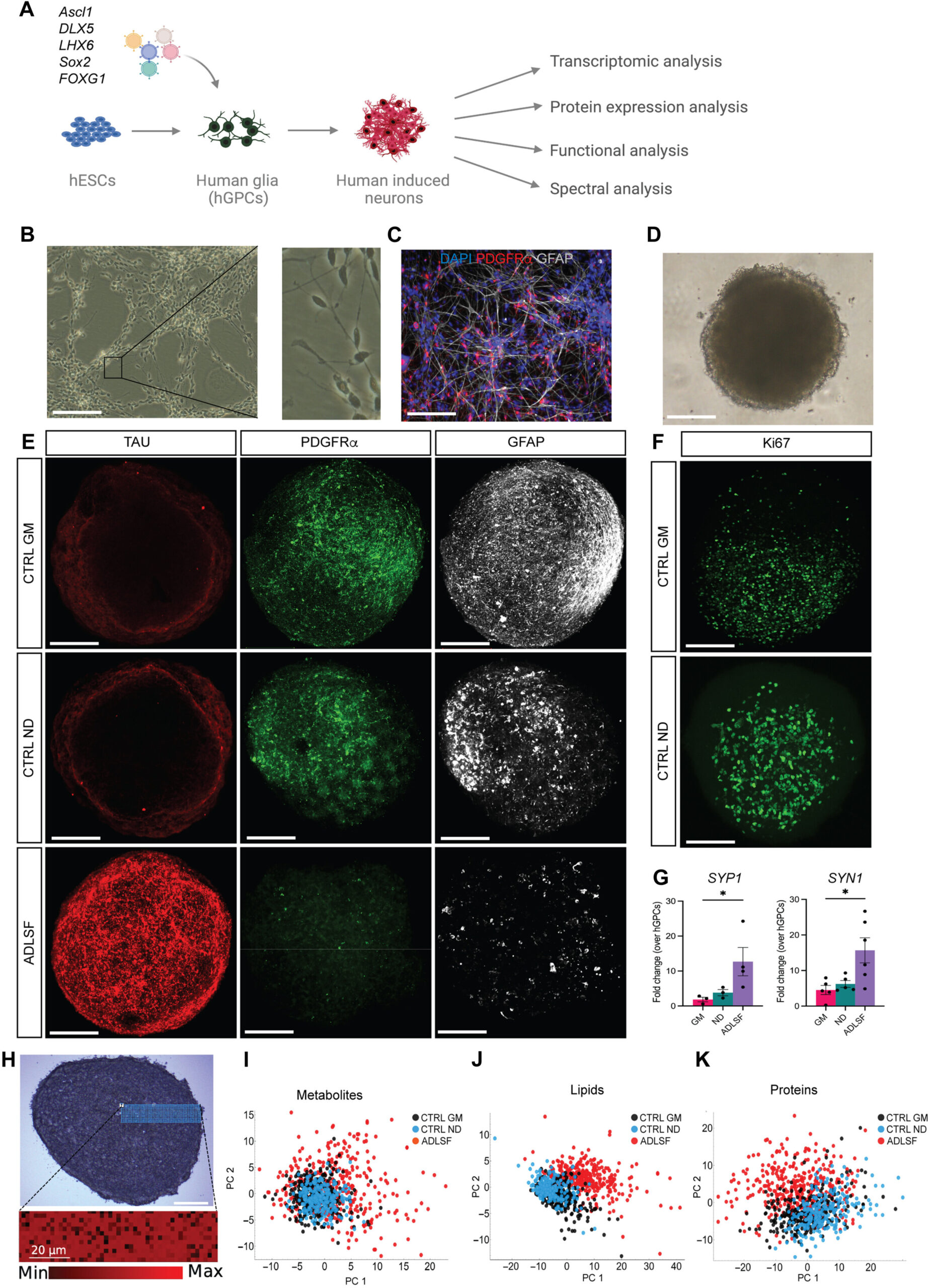

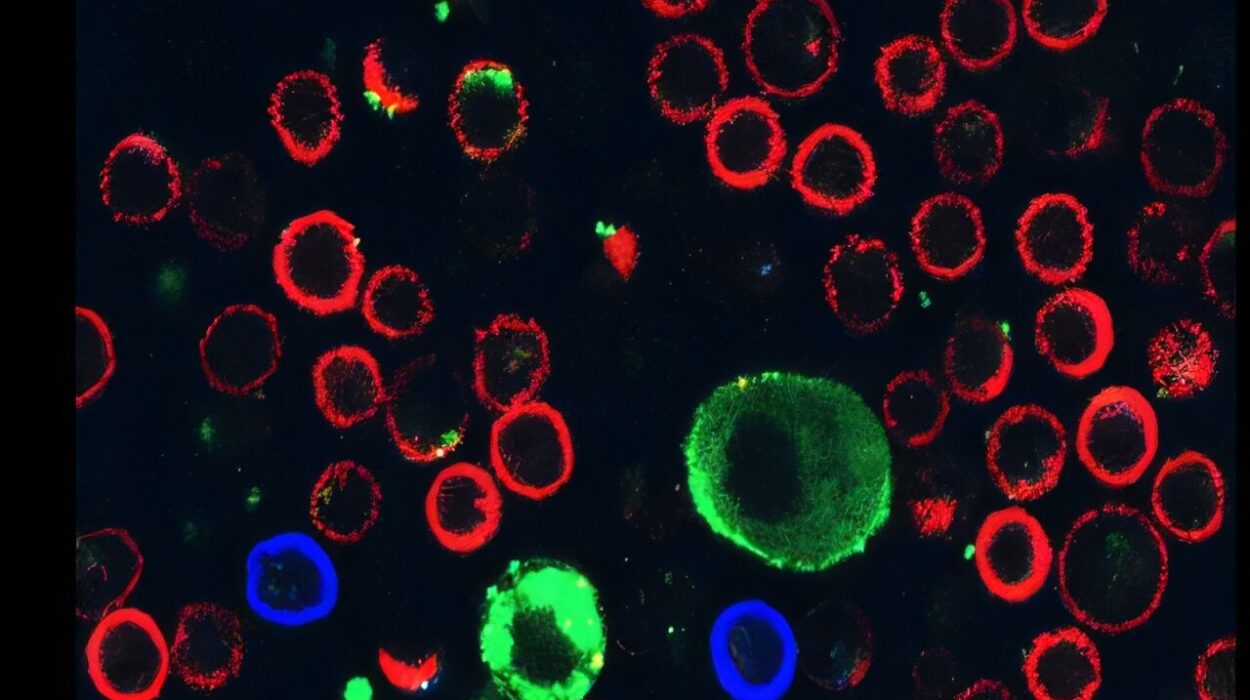

To find a solution for a broken brain, the researchers turned their attention away from the primary neurons and toward the glial cells. Often referred to as the brain’s support cells, glia are the silent architects that surround and protect neurons. In a groundbreaking study published in Science Advances, the team at Lund University revealed they had developed a method to directly reprogram these support cells into the missing parvalbumin neurons. This was not a simple task of moving cells around, but rather a fundamental transformation of a cell’s purpose and biological signature.

The work builds on the team’s earlier discoveries, but this recent breakthrough represents a significant leap forward. They have moved beyond theory into a realm where they can witness the birth of a specific type of neuron from a completely different cell type. “In our study, we have for the first time succeeded in reprogramming human glial cells into parvalbumin neurons –that resemble those that naturally exist in the brain. We have also been able to identify several key genes that seem to play a crucial role in the transformation,” says Daniella Rylander Ottosson, a researcher in regenerative neurophysiology at Lund University who led the study. By identifying these genetic keys, the team has unlocked the ability to turn a support cell into a high-speed regulator.

Bypassing the Blueprint of the Past

Traditionally, the way to “grow” new brain cells in a lab involved a long, winding detour through the world of stem cells. Researchers would typically take a cell, revert it to its most basic, embryonic state—a stem cell—and then try to coax it into becoming a specific type of neuron. However, parvalbumin cells presented a unique wall for scientists. In the natural development of a human fetus, these specific cells are formed quite late in the process. This late-stage arrival in the womb has made them incredibly difficult to replicate in a laboratory setting using stem cell methods. The timing was always off, and the results were often inconsistent.

The breakthrough at Lund University lies in its efficiency. Instead of taking the long “detour” through the stem-cell stage, the researchers found a way to take a shortcut. They realized they could skip the embryonic phase entirely and force a direct identity change. “By activating the correct genes, we force the glial cells to transform into parvalbumin cells, without the detour via stem cells. We hope it will be possible to improve the method using the new genes we have identified,” says Rylander Ottosson. This direct reprogramming is a much faster process, effectively commanding a glial cell to shed its old life and take on the mantle of a parvalbumin neuron almost instantly.

A New Rhythm for the Future

The implications of being able to manufacture these “rapid-braking” cells are vast and immediate. In the short term, this discovery provides a powerful new tool for medical science. Because these cells can be produced from a patient’s own biology, researchers can now create parvalbumin cells in the lab to study the specific disease mechanisms of schizophrenia and epilepsy in a way that was never before possible. It allows them to watch, in real-time, how these cells behave or fail within the context of a specific person’s genetic makeup.

But the long-term vision is even more ambitious. Rylander Ottosson hopes that their method of transforming glial cells into parvalbumin cells will eventually be able to help patients directly. The ultimate goal is to move beyond the lab and develop therapies that can replace lost or damaged brain cells directly inside a living human brain. If a patient’s brain has lost its rhythm due to the decay of its natural braking system, this technology could potentially allow doctors to reprogram the surrounding support cells to step up and fill the void.

This research matters because it offers a potential path toward healing the fundamental disruptions of the mind. For individuals living with epilepsy or schizophrenia, the brain’s “sound” has become distorted by overactivity and a lack of control. By mastering the art of cellular transformation, these researchers are not just creating new cells; they are finding a way to restore the brain’s essential balance. This work provides hope that one day, we will be able to reach into a disordered brain and give it back the conductors it needs to play a harmonious, rhythmic, and healthy tune once again.

Study Details

Christina A. Stamouli et al, A distinct lineage pathway drives parvalbumin chandelier cell fate in human interneuron reprogramming, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv0588