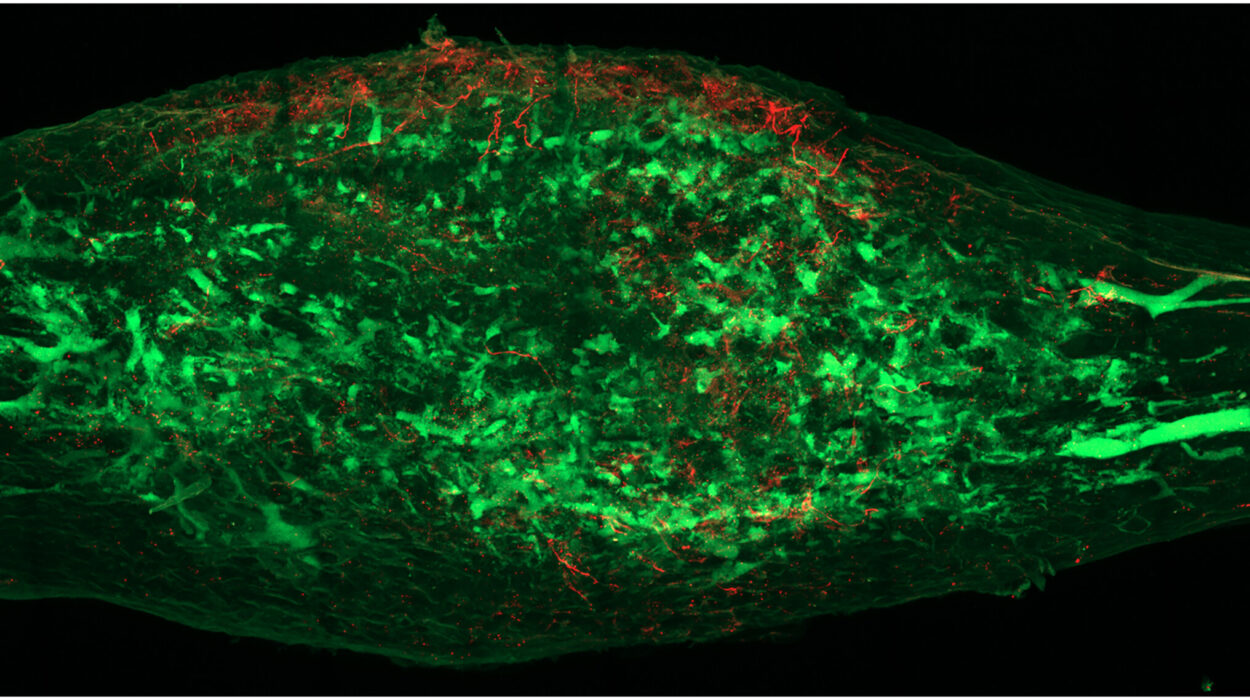

The human brain is protected by a delicate, plastic-wrap-like membrane known as the leptomeninges, a thin layer that encases the central nervous system. For most people, this shield does its job in quiet obscurity. But for those living with multiple sclerosis, or MS, this membrane can become the staging ground for a hidden, devastating conflict. In a new study led by the University of Toronto, researchers have peered into this “compartmentalized inflammation,” uncovering a biological signal that might finally explain why some patients experience a steady, irreversible decline while others do not.

The challenge of MS has always been its unpredictability. In Canada, where the disease strikes with some of the highest frequencies on earth, over 4,300 people receive a diagnosis every year. For many, the disease begins as a series of relapses and remissions—episodes of disability followed by periods of recovery. But for about ten percent of patients, the diagnosis is progressive from the very start, characterized by a gradual worsening of symptoms and a slow accumulation of disability. Even those who start with the relapsing-remitting form can eventually transition into this progressive phase.

As Jen Gommerman, a professor and chair of immunology at U of T’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine, points out, the medical community has long struggled to see into the future of these patients. “It’s been really hard to know who is progressing and who isn’t,” Gommerman explains. While science has provided tools to manage the flares of the early disease, the progressive stage remains a dark frontier.

Searching for a Map in the Gray Matter

The mystery of progressive MS is largely a mystery of the brain’s gray matter. Unlike the relapsing phase, which scientists have learned to manage with immunomodulatory drugs, the progressive phase involves a different kind of damage. “We have immunomodulatory drugs that can modulate the relapsing and remitting phase of the disease,” says Valeria Ramaglia, a scientist at the University Health Network’s Krembil Brain Institute. “But for progressive MS, the landscape is completely different. We have no effective therapies.”

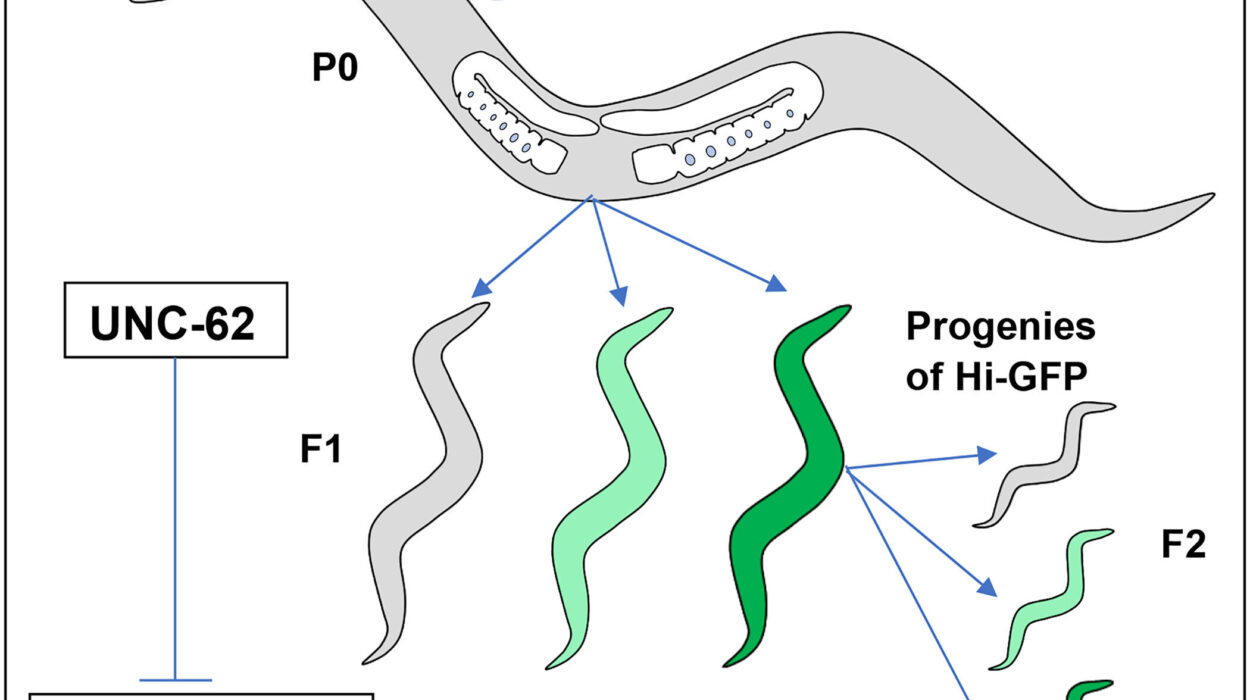

The primary obstacle has been a lack of visibility. Until now, the research field lacked a reliable model that could replicate the specific pathology of progressive MS. To solve this, the research team developed a new mouse model designed to mimic the injury to the brain’s gray matter. They focused their attention on the leptomeninges, where they suspected a “compartmentalized” fire was burning.

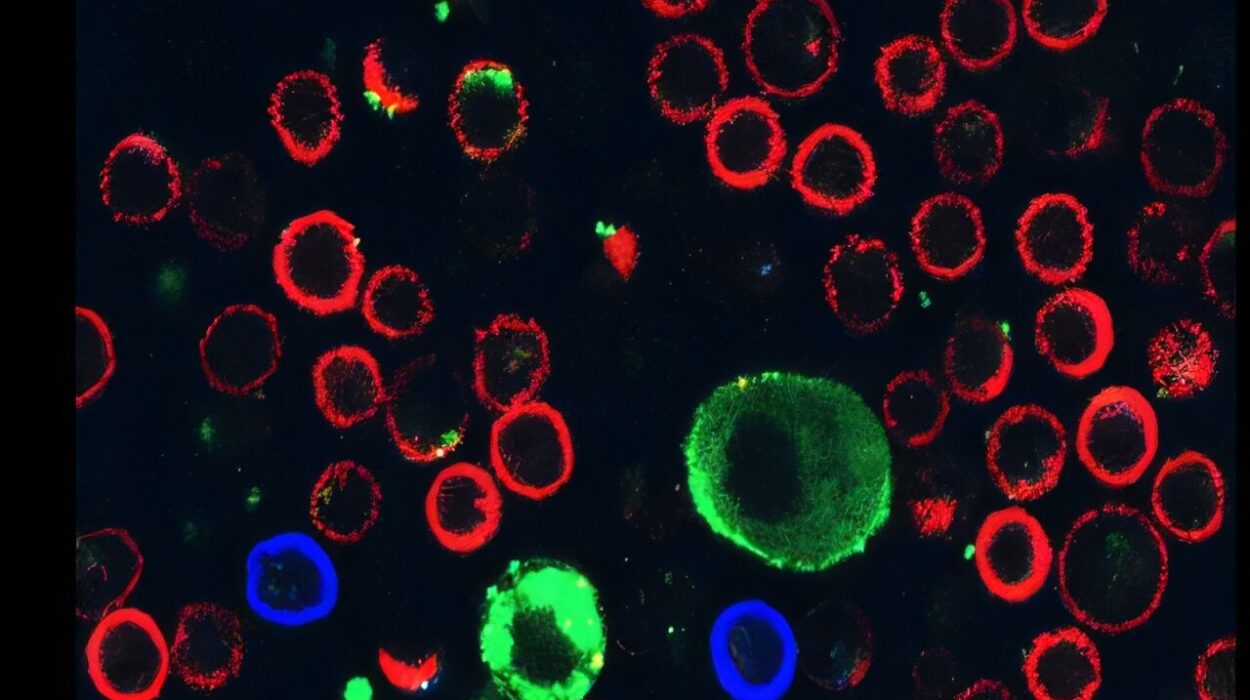

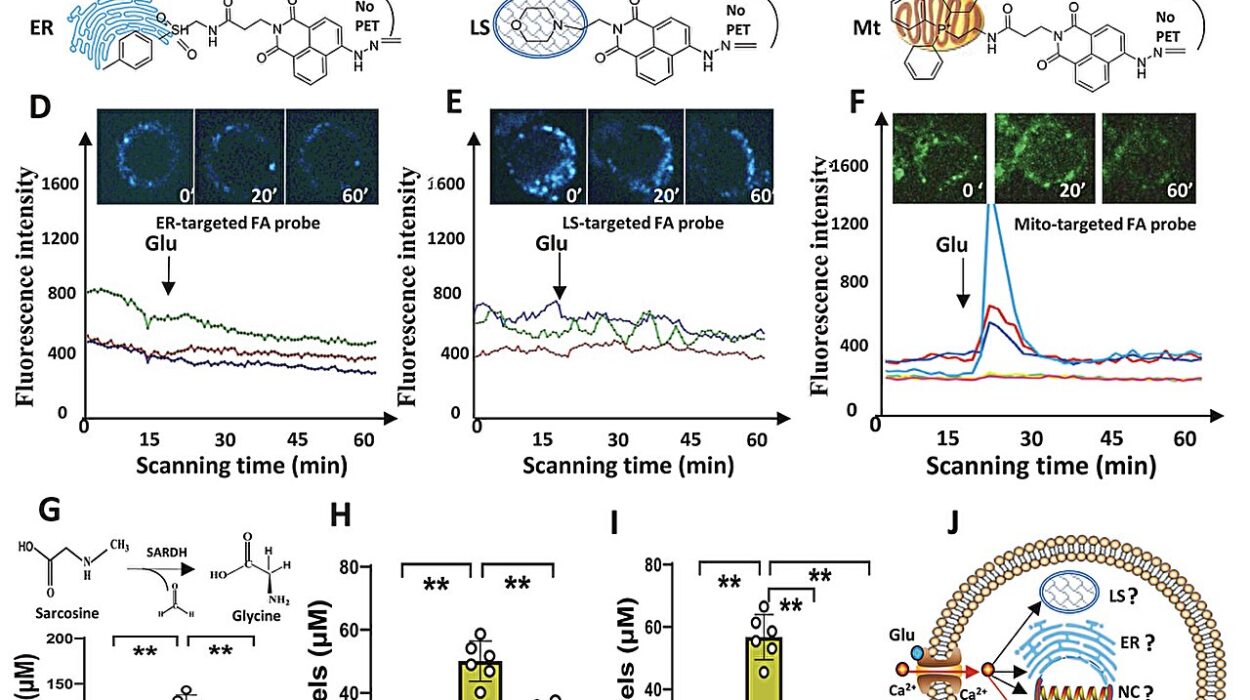

By observing these models, the researchers didn’t just see damage; they saw a specific chemical signature. They discovered a staggering 800-fold increase in an immune signal called CXCL13, occurring alongside significantly lower levels of a different immune protein known as BAFF. This dramatic shift in the chemical balance of the brain provided the first clue that they had found a way to measure the invisible inflammation driving the disease forward.

A Circuit Revealed and a Ratio Discovered

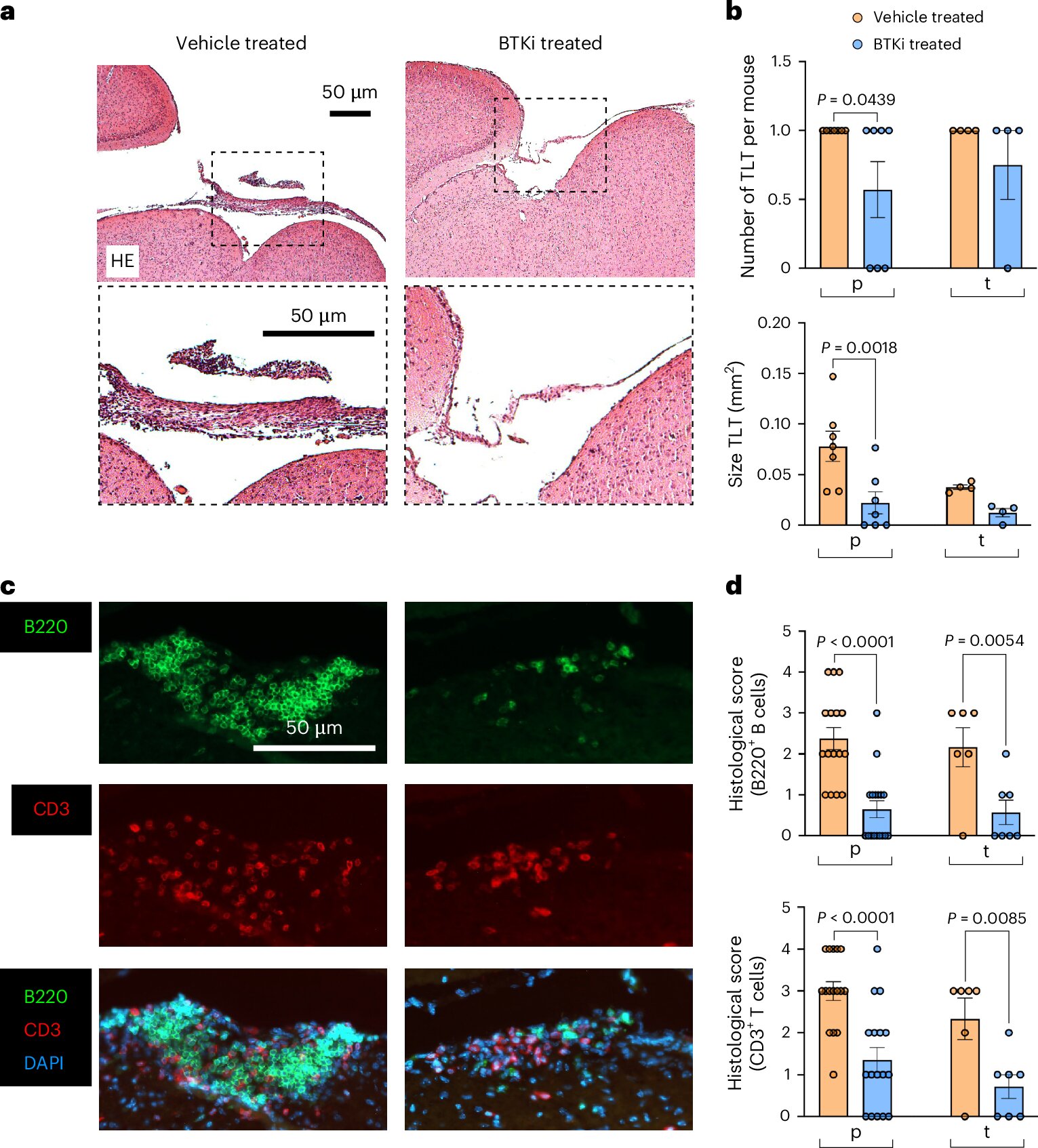

To test if they were on the right track, the researchers turned to a class of experimental treatments known as BTK inhibitors. These drugs are currently being tested in human clinical trials with the hope that they might finally offer a weapon against progressive MS. When the researchers applied these inhibitors to their mouse models, the results were striking. The drugs mapped out a specific circuit in the brain that led directly to gray matter injury and inflammation.

More importantly, the treatment appeared to reset the biological clock. The BTK inhibitors restored the levels of CXCL13 and BAFF back to what is typically seen in healthy mice. This discovery led the team to a groundbreaking hypothesis: the ratio between these two proteins—CXCL13 and BAFF—could serve as a surrogate marker, a “proxy” that tells doctors exactly how much inflammation is trapped within the membranes of the brain.

This ratio offered a potential solution to a frustrating problem in medical research. While BTK inhibitors have been tested in humans, the results have been mixed. Ramaglia suggests that this inconsistency might be because researchers didn’t know which patients were actually suffering from leptomeningeal inflammation. Without a way to detect it, clinical trials likely included people who didn’t have that specific feature, meaning they were unlikely to benefit. When their lack of response was averaged with those who did benefit, the positive results were “diluted,” making a potentially life-changing drug look less effective than it truly was.

From the Lab Bench to the Human Heart

The true test of any discovery made in a mouse model is whether it holds true in the complex reality of the human body. To find out, the researchers analyzed postmortem brain tissues from individuals who had lived with MS, as well as the cerebrospinal fluid of living patients. The results confirmed their theory: a high CXCL13-to-BAFF ratio was consistently associated with greater compartmentalized inflammation in the human brain.

This validation opens the door to a new era of precision medicine. “If we can use the ratio as a proxy to tell which patients should be treated with a drug that targets leptomeningeal inflammation, that can revolutionize the way we do clinical trials and how we treat patients,” says Ramaglia.

The collaboration between Gommerman and Ramaglia is moving forward into the next phase of discovery. They are now working alongside pharmaceutical companies to look back at the participants of previous BTK inhibitor trials. By checking the CXCL13-to-BAFF ratios of those patients, they hope to confirm that the people who responded most successfully to the drugs were indeed the ones with the highest ratios. Ramaglia is also looking toward the earliest stages of the disease, investigating whether these protein levels can predict at the very beginning of a patient’s journey who is destined to develop the progressive form of MS years later.

Why This Research Matters

This study represents a fundamental shift in how we understand and treat one of the most challenging forms of neurological disease. For decades, progressive MS has been a “black box” for clinicians—a stage of illness where symptoms worsen without a clear way to track the underlying biological cause or predict the speed of decline. By identifying the CXCL13-to-BAFF ratio, researchers have finally found a “biomarker,” a measurable signal that acts as a window into the brain’s internal environment.

The significance of this discovery lies in its potential to bring “precision medicine” to MS care. Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach that often fails, doctors may soon be able to use a simple test of the cerebrospinal fluid to determine if a patient’s brain is experiencing the specific type of inflammation that leads to permanent disability. This allows for the right drugs to be given to the right people at the right time, ensuring that clinical trials are more accurate and that patients aren’t given treatments that won’t work for them. Ultimately, this research provides a roadmap for stopping the “silent storm” in the brain’s membranes, offering hope for effective therapies where none currently exist.

Study Details

Lymphotoxin-dependent elevated meningeal 1 CXCL13:BAFF ratios drive grey matter injury, Nature Immunology (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41590-025-02359-5