Inside the intricate architecture of the human brain, a silent and devastating relay race is constantly underway in those living with Parkinson’s disease. For years, scientists have watched as a destructive protein moves from one healthy cell to the next, leaving a trail of degeneration in its wake. While we have long known the identity of the trespasser, the exact doors it uses to break into healthy neurons have remained a frustrating mystery. However, new research from the Yale School of Medicine has finally identified two specific proteins acting as the molecular gatekeepers of this disease, offering a potential roadmap to shutting the doors on Parkinson’s for good.

The Toxic Messenger That Refuses to Stay Put

The story of Parkinson’s disease is defined by the slow, relentless breakdown of the brain’s motor neurons. At the heart of this collapse is a single protagonist gone wrong: a protein known as α-synuclein. In a healthy brain, proteins fold into precise shapes to perform their duties, but in Parkinson’s, α-synuclein misfolds into a distorted, toxic version of itself. This misfolded protein is considered “the pathologic hallmark of Parkinson’s disease,” according to Stephen Strittmatter, MD, Ph.D., the Vincent Coates Professor of Neurology at Yale.

The true danger of α-synuclein lies in its ability to travel. It does not simply stay within the cell where it first appears. Instead, as a neuron dies, the misfolded protein escapes and migrates to neighboring healthy cells. Once inside its new host, it triggers more misfolding, creating a domino effect that spreads through the brain. As this toxic wave moves, the patient’s physical reality shifts. Tremors begin to shake the hands, balance becomes precarious, and movement slows to a crawl. The more the protein spreads, the more the symptoms worsen, yet for decades, the “how” of this migration remained a black box. “If we understood how it gets into neurons, we could perhaps block or slow down the progression of the disease,” Strittmatter explains. “We need to understand the molecular mechanism of how it spreads.”

Searching Through Thousands of Molecular Keys

To solve the mystery of how α-synuclein infiltrates healthy neurons, the Yale research team had to conduct a massive search. They hypothesized that the misfolded protein was not just drifting into cells by accident, but was instead binding to specific surface proteins—acting like a key finding a lock. To find these locks, the researchers created an exhaustive experiment involving 4,400 different batches of cells. Each batch was engineered to express a different cell surface protein, creating a vast library of potential entry points.

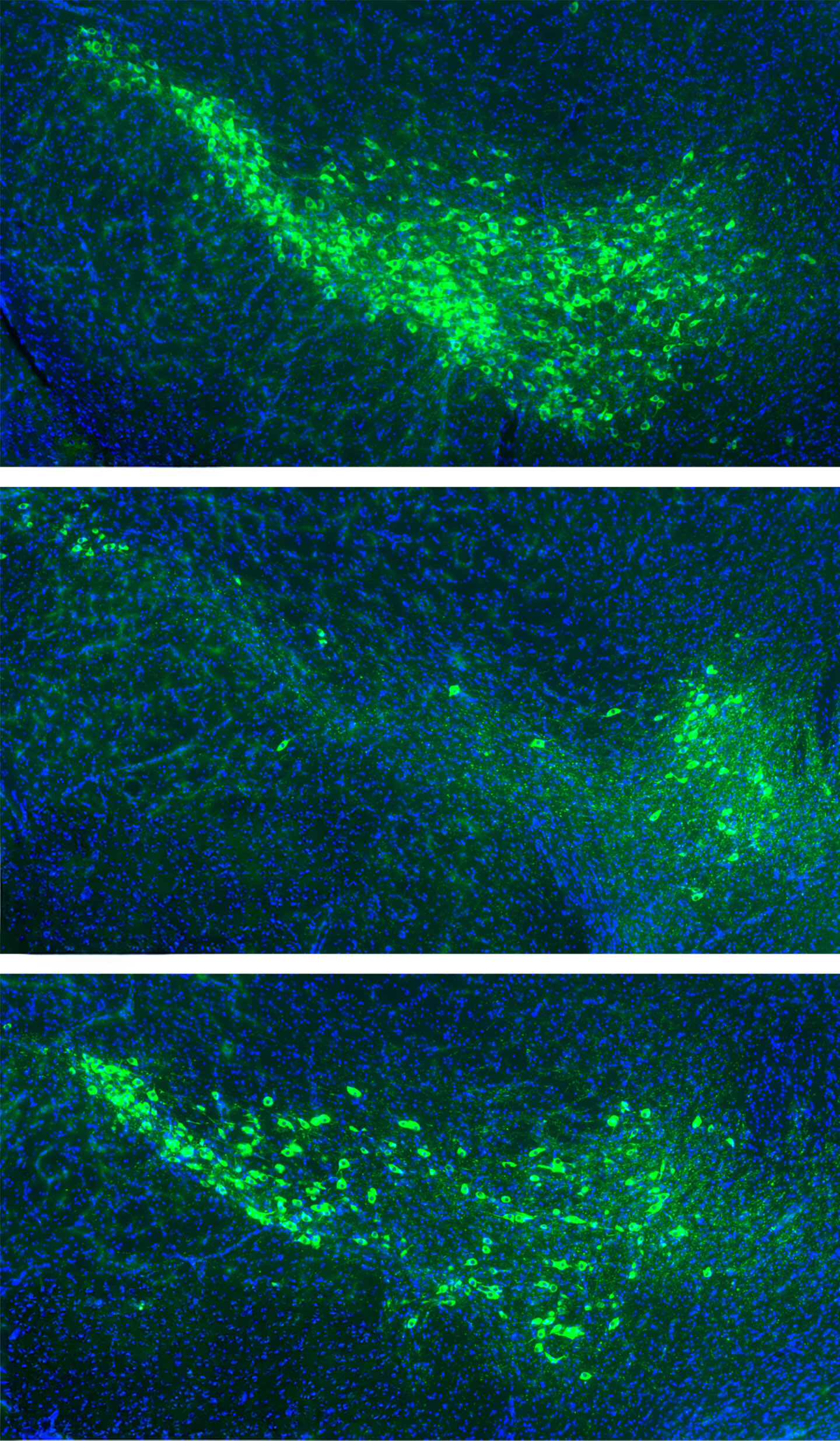

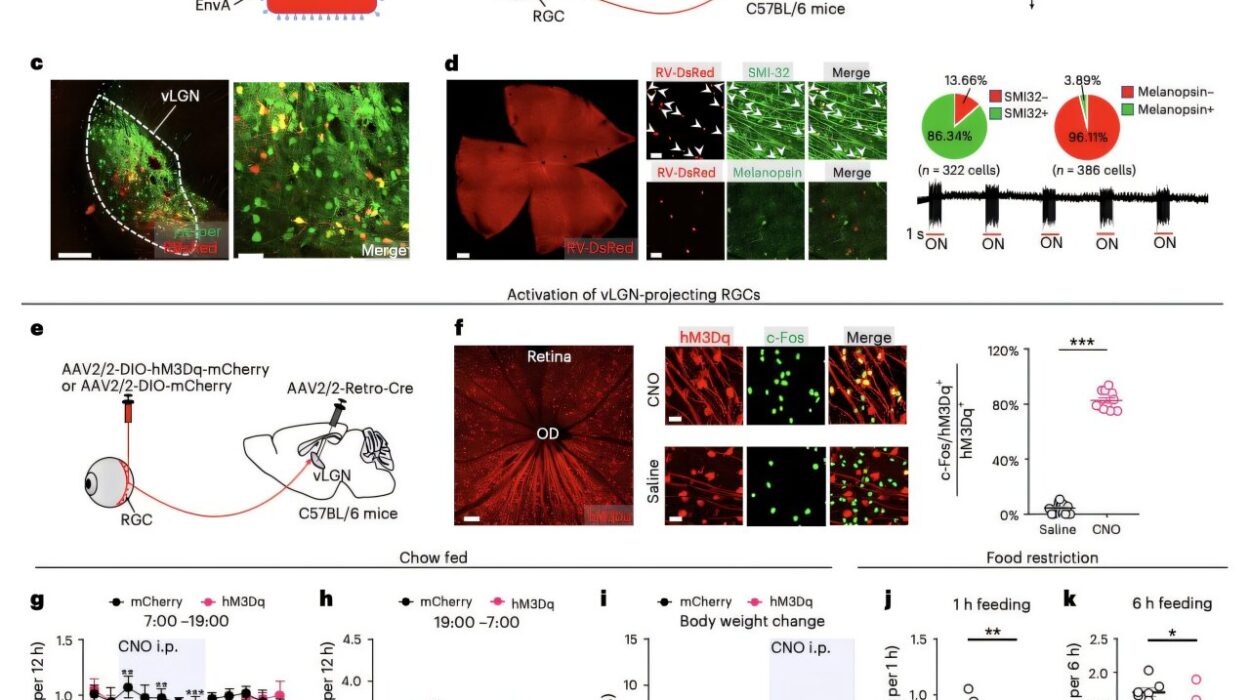

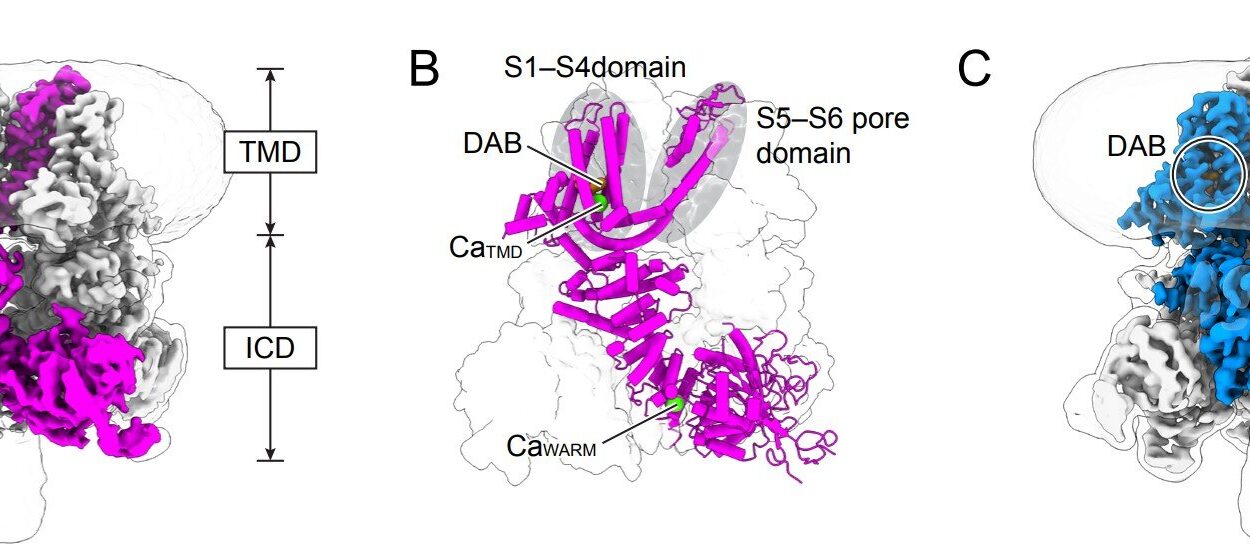

The team then introduced the misfolded α-synuclein to these thousands of samples to see which ones would catch the protein. The vast majority of the proteins ignored the intruder entirely. However, out of the thousands tested, 16 proteins showed a clear affinity for the misfolded α-synuclein. Among this small group of suspects, two stood out because they are naturally found in the human dopamine neurons of the substantia nigra. This specific region of the brain is the ground zero for Parkinson’s disease—the area that degenerates most significantly as the condition progresses. These two proteins, named mGluR4 and NPDC1, appeared to be the primary culprits, actively transporting the toxic α-synuclein across the cell membrane and into the interior of the neuron.

Closing the Gates to Protect the Brain

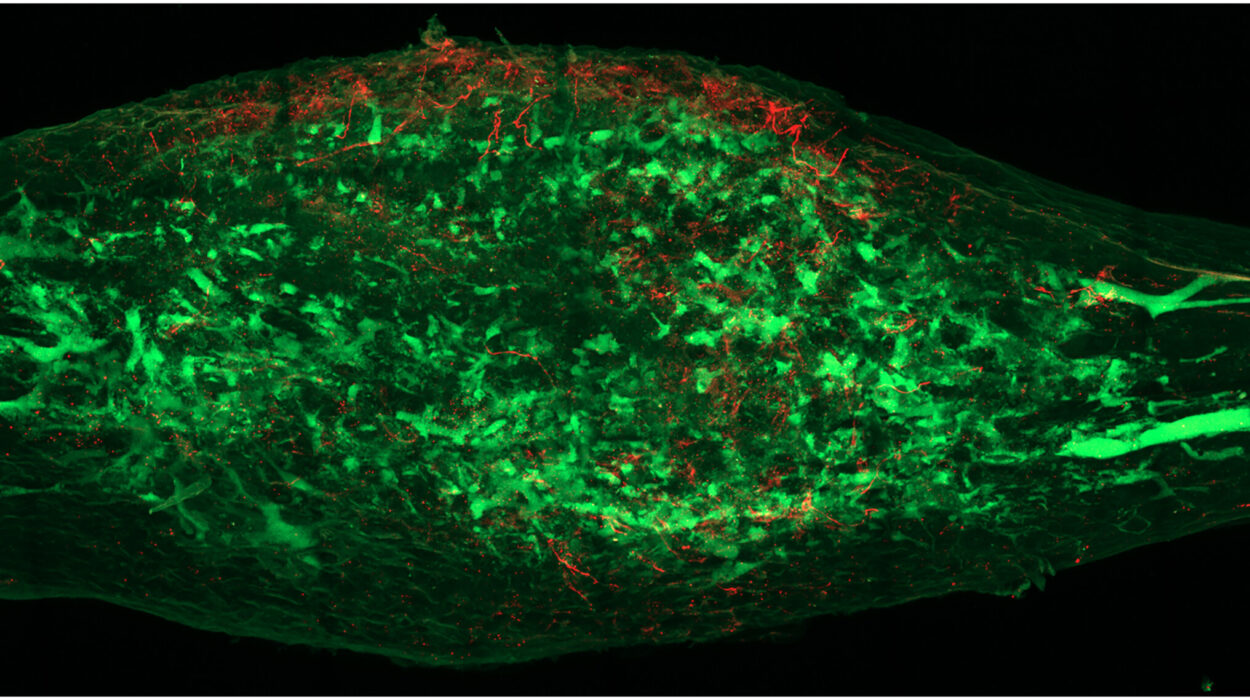

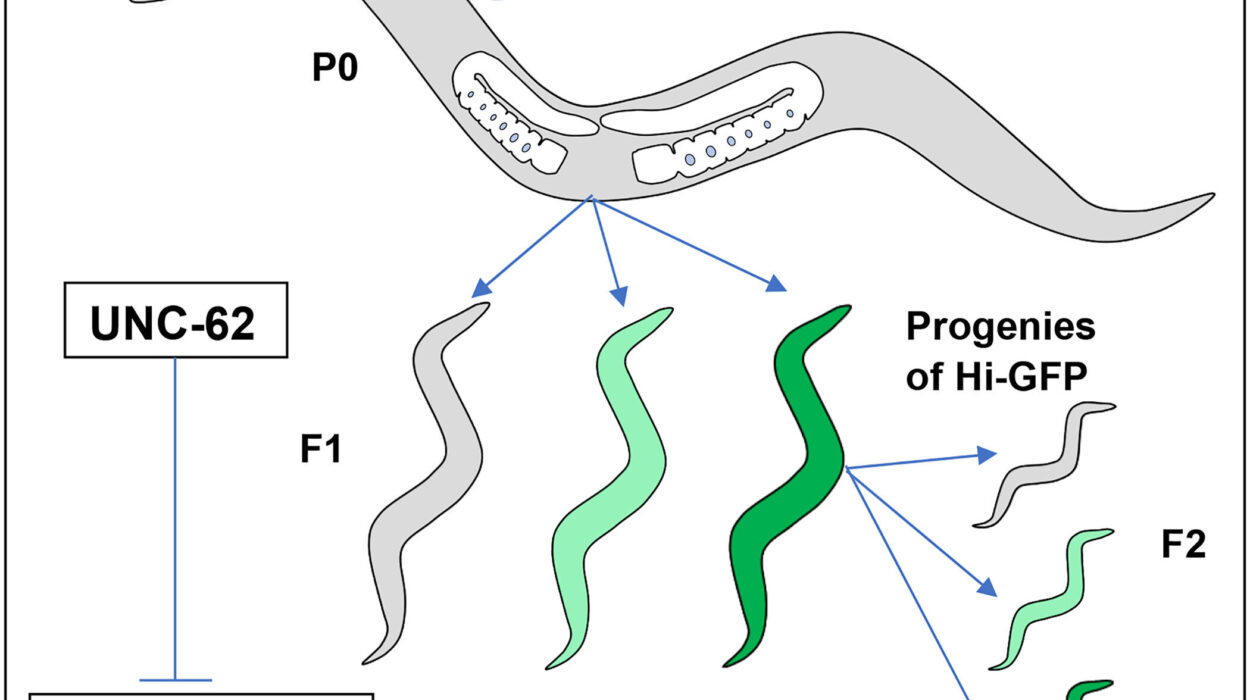

Identifying these proteins in a laboratory dish was only the first step. To see if mGluR4 and NPDC1 were truly the engines driving the disease’s progression, the researchers turned to mouse models. They utilized genetic engineering to create mice that lacked functional copies of either protein, essentially removing the “locks” from the surfaces of their brain cells. They then introduced the misfolded α-synuclein to see if the disease could still take hold.

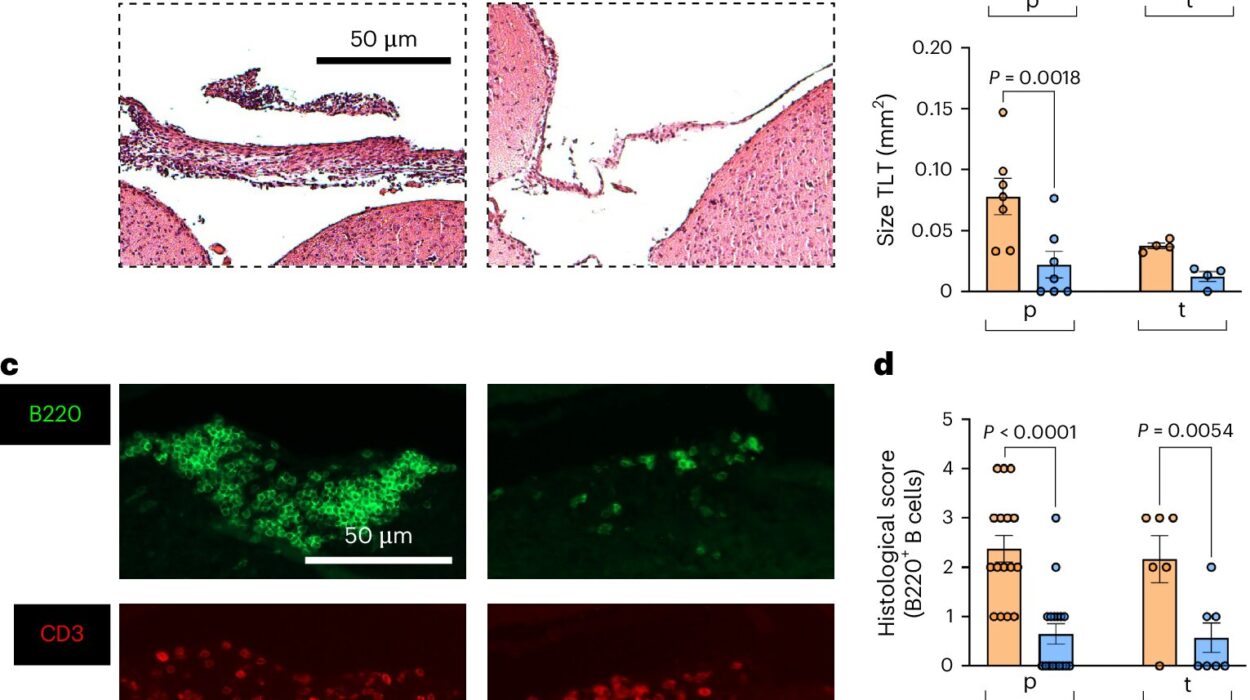

The results were striking. In regular mice, the introduction of the misfolded protein led to its accumulation throughout the brain, and the animals soon developed the tell-tale motor symptoms associated with Parkinson’s. However, the mice without working mGluR4 or NPDC1 were remarkably protected. Because the “gates” were gone, the toxic protein could not easily enter the healthy neurons. Furthermore, when the researchers knocked out the genes for these two proteins in mice that already had a model of Parkinson’s, they observed a reduction in the progression of symptoms and a lower risk of death. These experiments strongly suggested that mGluR4 and NPDC1 work in tandem to facilitate the spread of the disease.

Why Identifying These Gatekeepers Changes Everything

This discovery represents a fundamental shift in how we approach one of the most common neurodegenerative challenges in the United States. Currently, the Parkinson’s Foundation estimates that 1.1 million Americans are living with the disease, with nearly 90,000 new diagnoses every year. As the American population ages, these numbers are expected to climb significantly, placing an even greater urgency on the search for a cure. Up until now, most medical interventions have focused on managing symptoms—trying to steady the tremors or improve movement after the damage has already been done—rather than stopping the underlying destruction.

The identification of mGluR4 and NPDC1 changes the objective from symptom management to disease modification. By targeting these specific proteins, scientists may be able to develop treatments that physically block the path of α-synuclein. “We have an aging population. How we can stop or slow neurons from dying is an enormous problem,” says Strittmatter. “This is really the time to make some inroads into figuring out how to slow it down.” If researchers can find a way to interfere with these molecular gates in humans, it could lead to the first generation of therapies that do not just mask the effects of Parkinson’s, but actually halt its march through the brain, preserving the health and mobility of millions of people.

Study Details

Azucena Perez-Canamas et al, mGluR4–NPDC1 complex mediates α-synuclein fibril-induced neurodegeneration, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-67731-3