Deep within the complex architecture of the brain, a subtle dance between light and appetite is unfolding. For years, science has understood that the world around us—the hum of a refrigerator, the glare of a midday sun, or the dim glow of a smartphone—does more than just provide sensory information. It seeps into our biology, shifting our internal clocks and altering how we feel. Researchers have long noted that noise and light can disrupt our sleeping patterns, throw our circadian rhythms into disarray, and even tug at the strings of our metabolism and stress levels. Yet, a specific mystery remained: why does the simple presence of bright light seem to tell the body it is time to stop eating?

A Ray of Hope in the Shadows of Modern Health

Bright light therapy is not a new concept in the halls of medicine. Doctors have successfully used intense artificial light, often for thirty minutes or more a day, to lift the heavy fog of seasonal affective disorder and to guide those struggling with insomnia or depression back toward a balanced life. But as researchers at Jinan University and other institutions in China began to look closer, they noticed a curious side effect. This same light therapy appeared to have an anti-obesity potential, helping to prevent weight gain or even facilitate weight loss. The missing piece of the puzzle was the “how.” The biological bridge between the eye and the stomach remained hidden in the dark.

“Environmental light regulates nonimage-forming functions like feeding, and bright light therapy shows anti-obesity potential, yet its neural basis remains unclear,” wrote Wen Li, Xiaodan Huang, and their colleagues. Driven by this uncertainty, the team set out to map the hidden circuitry of the brain, hoping to discover exactly how a beam of light could influence the urge to consume.

Decoding the Language of the Eye

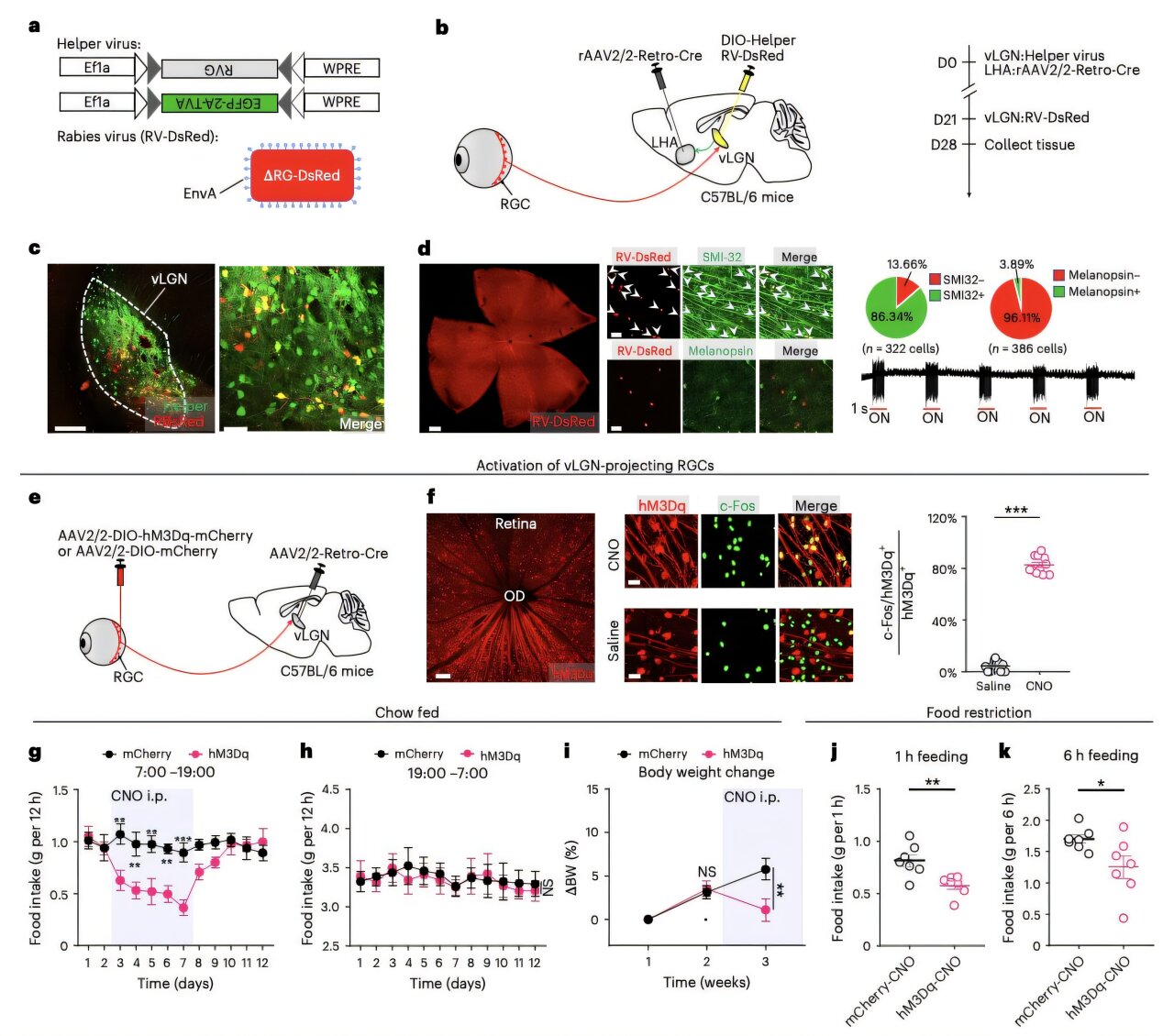

To uncover this secret pathway, the researchers designed a meticulous experiment involving adult mice, creatures whose physiological responses often mirror the foundational mechanics of the human brain. The mice were placed into a controlled environment where the day was split perfectly: twelve hours of light followed by twelve hours of velvety darkness. However, the intensity of that light was the key variable. Some mice lived under the softest glow, while others were bathed in light reaching intensities of 1,000, 3,000, or even 5,000 lux.

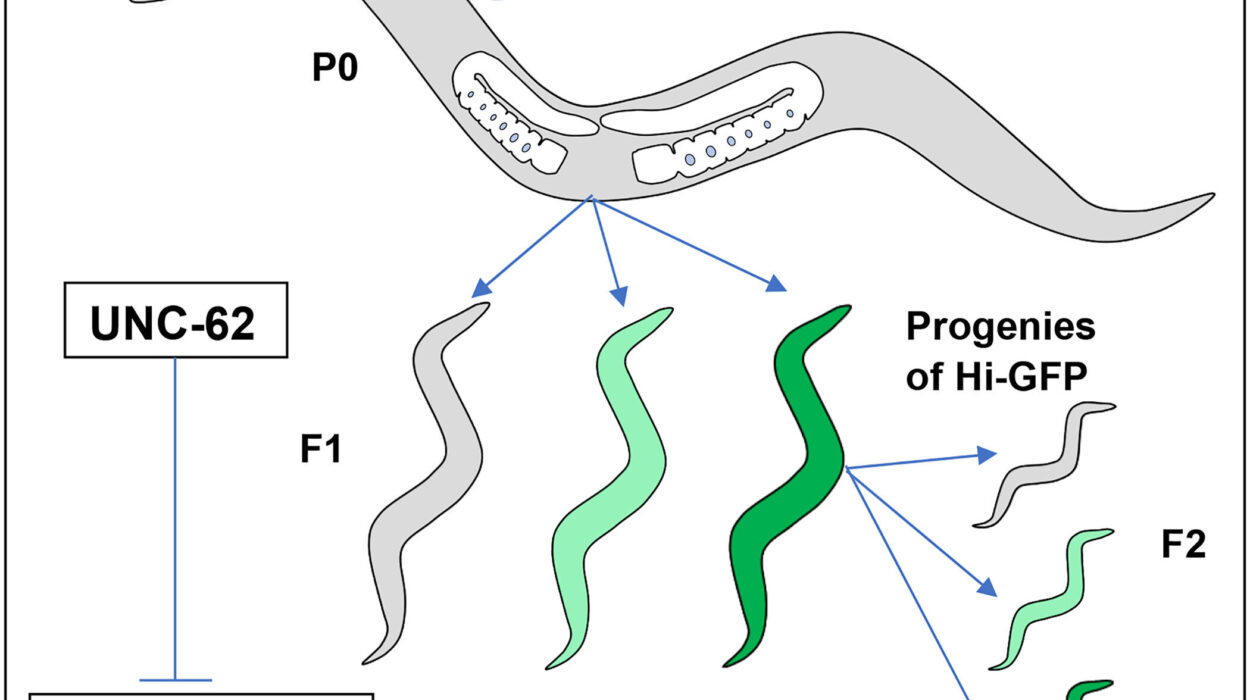

As the days passed, a clear pattern emerged from the data. The mice exposed to the brightest light began to behave differently than their counterparts in the dim. They ate less. They gained less weight. It was as if the light itself was acting as an invisible barrier to overconsumption. To find out why, the scientists turned to chemogenetic techniques—cutting-edge methods that allow researchers to toggle specific brain cells on and off using genetic alterations and chemical triggers. They weren’t just watching the mice; they were listening to the electrical conversations happening inside their heads.

The Secret Path from Sight to Satiety

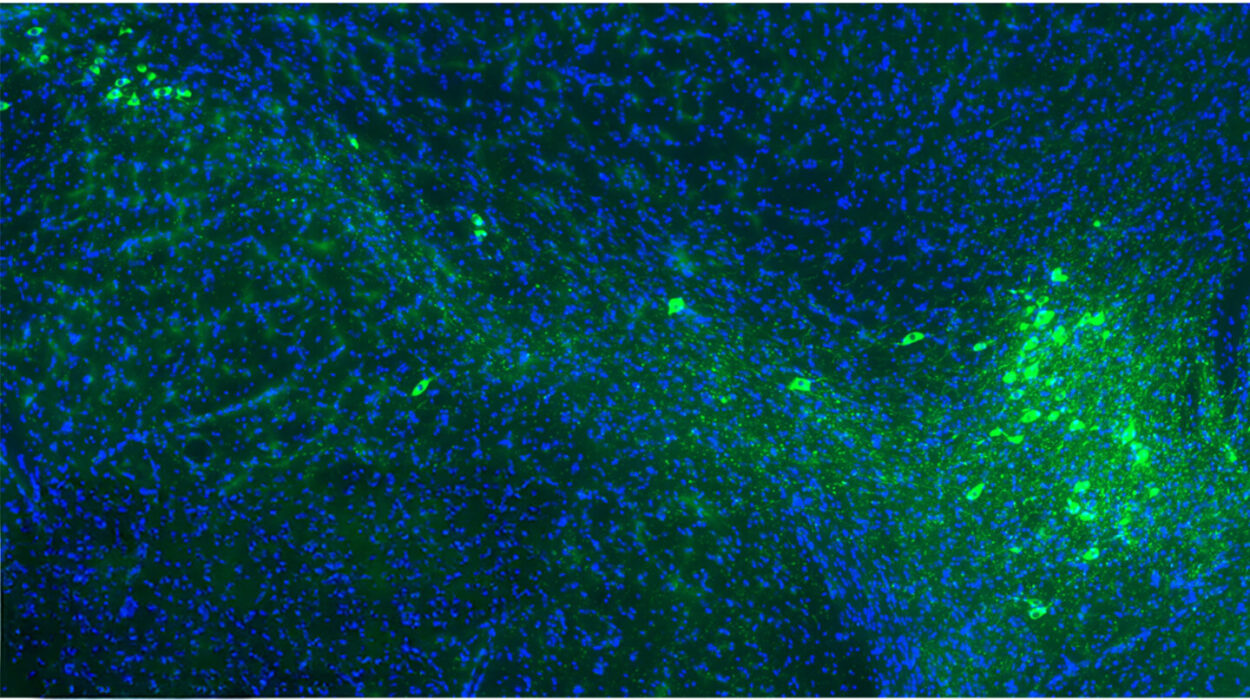

The team’s investigation led them to a specific neural highway that begins in the retina and ends in the lateral hypothalamic area, or LHA, a region of the brain long known to be a command center for feeding behavior. They discovered that the process begins with a very specific group of cells in the eye called SMI-32-expressing ON-type retinal ganglion cells. These cells don’t just help the mouse see the world; they send a specialized signal deep into the brain to a region called the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus, or vLGN.

“Specifically, a subset of SMI-32-expressing ON-type retinal ganglion cells innervate GABAergic neurons in the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus (vLGN), which in turn inhibits GABAergic neurons in the LHA,” the researchers explained. This chain reaction is a masterclass in biological precision. When the bright light hits the eye, it activates the vLGN, which then sends a “stop” signal to the LHA. By inhibiting the neurons in the LHA that typically drive the urge to eat, the light effectively mutes the body’s hunger signals. “Activation of both vLGN-projecting retinal ganglion cells and the vLGN-to-LHA projection is sufficient to suppress food consumption and attenuate weight gain,” the team noted in their findings.

Illuminating the Future of Wellness

This discovery does more than just explain a quirk of biology; it provides a concrete, physical map of how our environment dictates our health. For the first time, scientists have “direct evidence that the suppressive effects of bright light treatment on food consumption and weight gain rely on the activation of the retina–vLGN–LHA pathway.” This isn’t just about mice in a lab; it is about understanding the fundamental visual circuits that govern how all mammals interact with food. “Together, our results delineate an LHA-related visual circuit underlying the food consumption-suppressing and weight gain-attenuating effects of bright light treatment,” the authors concluded.

The implications of this research are profound. In a world where obesity remains a significant global challenge, the realization that light can be used as a tool for metabolic health opens doors to entirely new kinds of treatments. Rather than relying solely on traditional interventions, the future might involve carefully timed and calibrated light exposure to help people maintain a healthy weight. By shining a light on the vLGN-LHA pathway, this study offers a bright new perspective on how we might one day manage weight loss, simply by changing the way we see the world.

Study Details

Wen Li et al, Bright light exposure suppresses feeding and weight gain via a visual circuit linked to the lateral hypothalamus, Nature Neuroscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-025-02156-1.