In the quiet layers of the human skin, a silent and sophisticated battle is unfolding, one that has long eluded the full understanding of modern science. For years, researchers have watched as melanoma, the most lethal form of skin cancer, manages to bypass the body’s most potent defenses with an almost eerie ease. It is a disease defined by its transition from a localized threat to a systemic invader, moving from the skin’s outer epidermis into the deeper dermis, where it hitches a ride on the lymphatic and blood systems to reach distant organs. But the question of how these cancer cells managed to survive the journey through an environment teeming with aggressive immune cells remained a haunting mystery. Now, a breakthrough led by Professor Carmit Levy and an international team of collaborators has pulled back the curtain on this microscopic warfare, revealing that the cancer does not just hide from the immune system—it actively strikes back.

The Secret Signals in the Skin

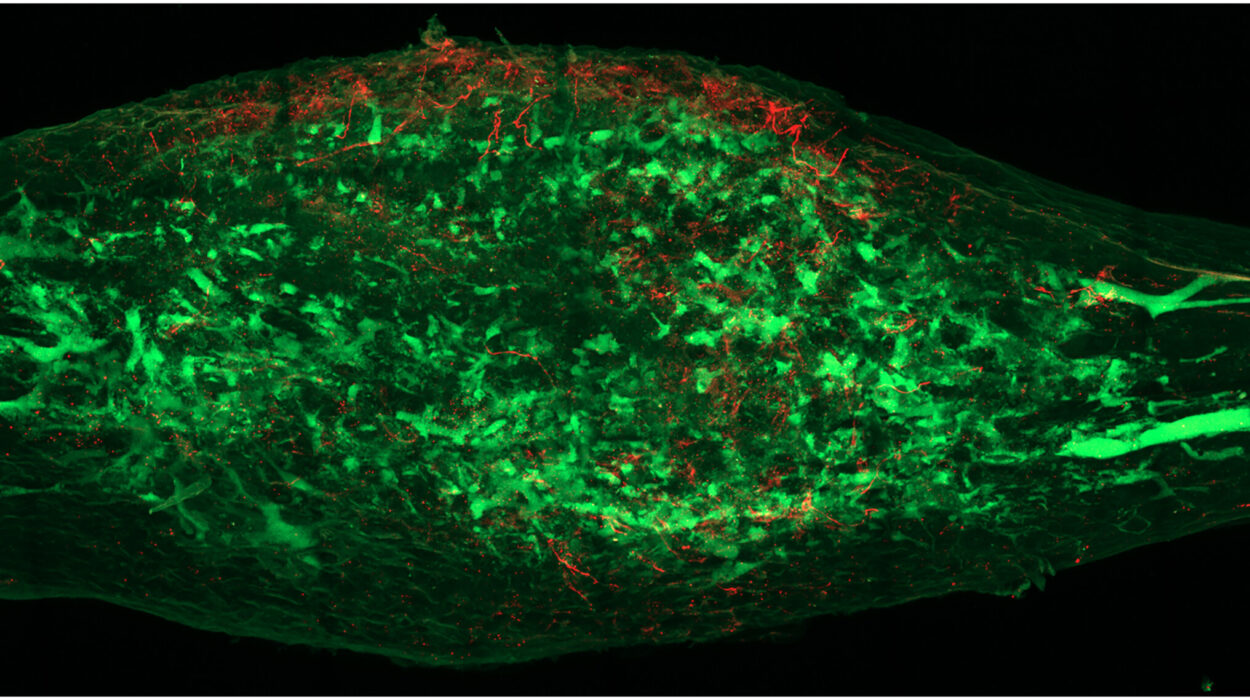

To understand this discovery, one must first look at the earliest stages of the disease. In the beginning, the cancer begins as a group of melanocytic cells that have lost their internal rhythm, dividing without restraint in the epidermis. As Professor Levy had discovered in previous research, these growing melanoma cells do not keep to themselves. Even while confined to the surface, they begin preparing the body for their eventual expansion. They do this by secreting tiny, bubble-shaped containers known as extracellular vesicles, or melanosomes. These microscopic messengers travel deep into the skin, penetrating dermal cells and blood vessels to create a “favorable niche”—essentially a welcoming environment—for the cancer to inhabit once it begins to spread.

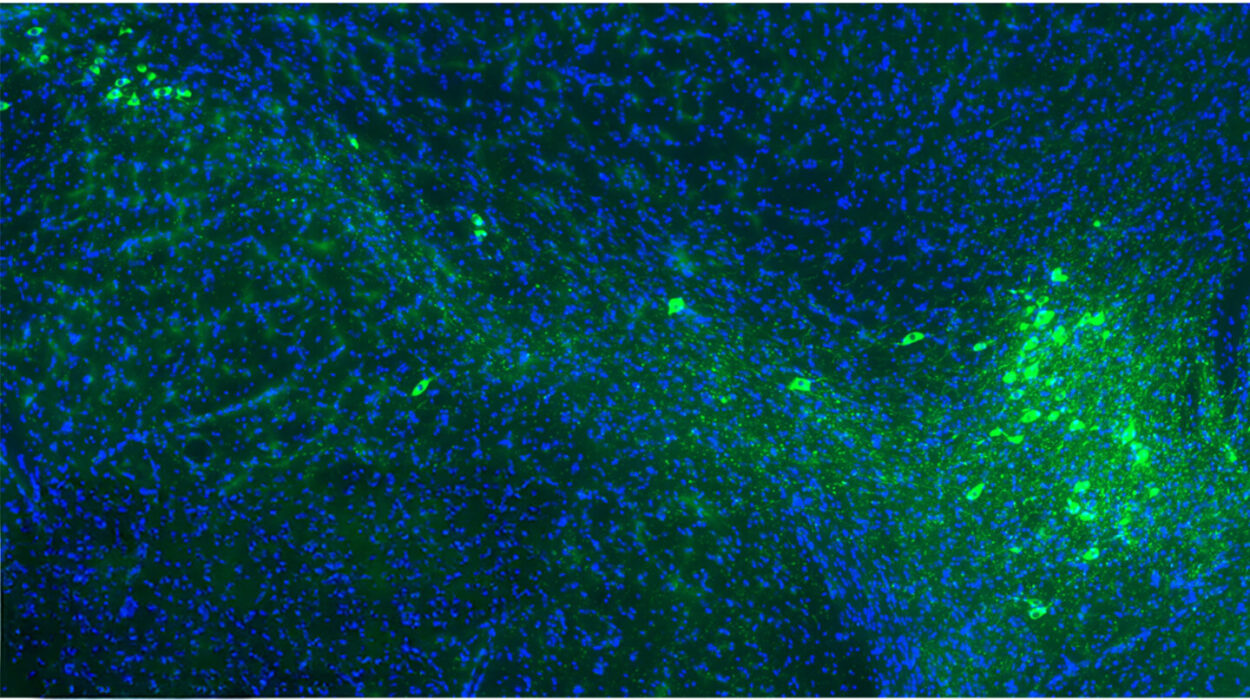

However, as Professor Levy and her team at Tel Aviv University’s Gray Faculty of Medical & Health Sciences looked closer at these vesicles, they noticed something that didn’t quite fit the existing narrative of cancer growth. These bubbles were not just construction crews building a new home; they were armed. While examining the membrane of the vesicles, Levy spotted a specific ligand—a molecule designed to bind with a very particular type of receptor. This receptor was not found on skin cells or blood vessels, but exclusively on lymphocytes, the elite soldiers of the immune system capable of killing cancer cells upon direct contact.

An Unexpected Shield Becomes a Weapon

The realization sparked a radical new theory. Professor Levy began to wonder if the cancer was using these tiny bubbles to initiate contact with the immune system before the immune cells could ever reach the tumor itself. “This was an innovative and odd idea, and we started investigating it in the lab,” Levy explains. “When we got more and more evidence that this idea was correct, I spoke with colleagues around the world, and invited them to join and contribute their expertise.” This call for collaboration brought together minds from Harvard, the Weizmann Institute, and pathology departments across Europe and Israel, all focused on deciphering this strange behavior.

As the data poured in from labs in Zurich, Belgium, Paris, and beyond, the picture became clear. The melanoma cells were not merely shedding waste; they were launching a preemptive strike. By firing these vesicles toward the approaching lymphocytes, the cancer was able to intercept its attackers mid-flight. When the ligand on the vesicle latches onto the receptor on the immune cell, it creates a catastrophic disruption. “And the achievement is enormous,” says Levy. “We discovered that the cancer essentially fires these vesicles at the immune cells that attack it, disrupting their activity and even killing them.” It is a form of biological paralysis that leaves the immune system’s most effective killers helpless, effectively clearing a path for the cancer to invade the rest of the body.

Turning the Tide of the Invisible War

This discovery changes the way scientists view the “conversation” between a tumor and the body. Instead of the immune system failing to recognize the cancer, it appears the immune system is being actively silenced by these bubble-shaped decoys. This realization has profound implications for how we might treat melanoma in the future. If the cancer’s primary defense is this “counterattack” via vesicles, then the goal of medicine becomes finding a way to armor the immune system or disarm the vesicles themselves.

Professor Levy is optimistic about the future of this research, though she maintains the careful perspective of a scientist. “We still have a great deal of work ahead of us, but it is already clear that this discovery can have far-reaching therapeutic implications,” she says. “It will enable us to strengthen immune cells so they can withstand the melanoma’s counterattack. In parallel, we can block the molecules that enable vesicles to cling to immune cells, thereby exposing the cancer cells and making them more vulnerable. Either way, this study opens a new door to effective immunotherapeutic intervention.”

Why This Discovery Changes Everything

The significance of this research lies in its potential to transform one of the most difficult challenges in oncology: immunotherapy resistance. By identifying the specific mechanism—the extracellular vesicles—that melanoma uses to paralyze lymphocytes, researchers now have a tangible target for new drugs. If scientists can successfully block the ligand on these vesicles or prevent the vesicles from binding to immune receptors, they can essentially “unmask” the cancer. This would allow the body’s natural defenses to function as they were intended, recognizing and destroying the tumor cells without being neutralized before they can finish the job. For patients facing the deadliest form of skin cancer, this research offers more than just a new piece of biological data; it offers the blueprint for a new generation of treatments that could finally turn the tide in the body’s favor.

Study Details

Yoav Chemla et al, HLA export by melanoma cells decoys cytotoxic T cells to promote immune evasion, Cell (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.11.020