Deep within the intricate architecture of the human mind, a silent transformation occurs when the weight of the world becomes too heavy to bear. For decades, science has understood that stress acts as a primary catalyst for depression—a condition that strips away the vibrancy of life, replacing it with a persistent, heavy sadness and a loss of interest in the very things that once brought joy. Yet, the bridge between an external stressful event and the internal biological collapse has remained shrouded in mystery. We knew that stress led to depression, but we didn’t fully understand the chemical language the brain used to translate that pressure into despair.

The Invisible Saboteur Rising Within

A groundbreaking investigation led by researchers at Wenzhou Medical University and Capital Medical University has recently pulled back the curtain on a surprising chemical suspect. While most of us recognize formaldehyde as a pungent substance used in laboratories or industrial settings, it is also a small, highly reactive chemical produced naturally within our own bodies as a byproduct of breaking down DNA, RNA, and proteins.

Scientists have long known that breathing in formaldehyde from the environment could lead to depressive symptoms, but they had never confirmed if the formaldehyde we create ourselves could do the same. As the research team began to trace the chemical footprints of stress, they discovered that the body’s own metabolic processes could turn against it. “Surprisingly, the administration of FA causes depressive symptoms in both animals and humans, though whether endogenous FA induces depression is unclear,” wrote researchers Yiqing Wu, Yonghe Tang, and their colleagues. “We report that stress-derived FA promotes depression onset.”

A Chemical Collision in the Heart of Memory

To understand how this internal chemical could trigger a mental health crisis, the researchers turned their attention to the hippocampus. This curved, almond-like structure tucked deep within the brain is the command center for memory and the regulation of emotions. In many patients suffering from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), the hippocampus shows signs of physical damage, appearing smaller or less active than it should be.

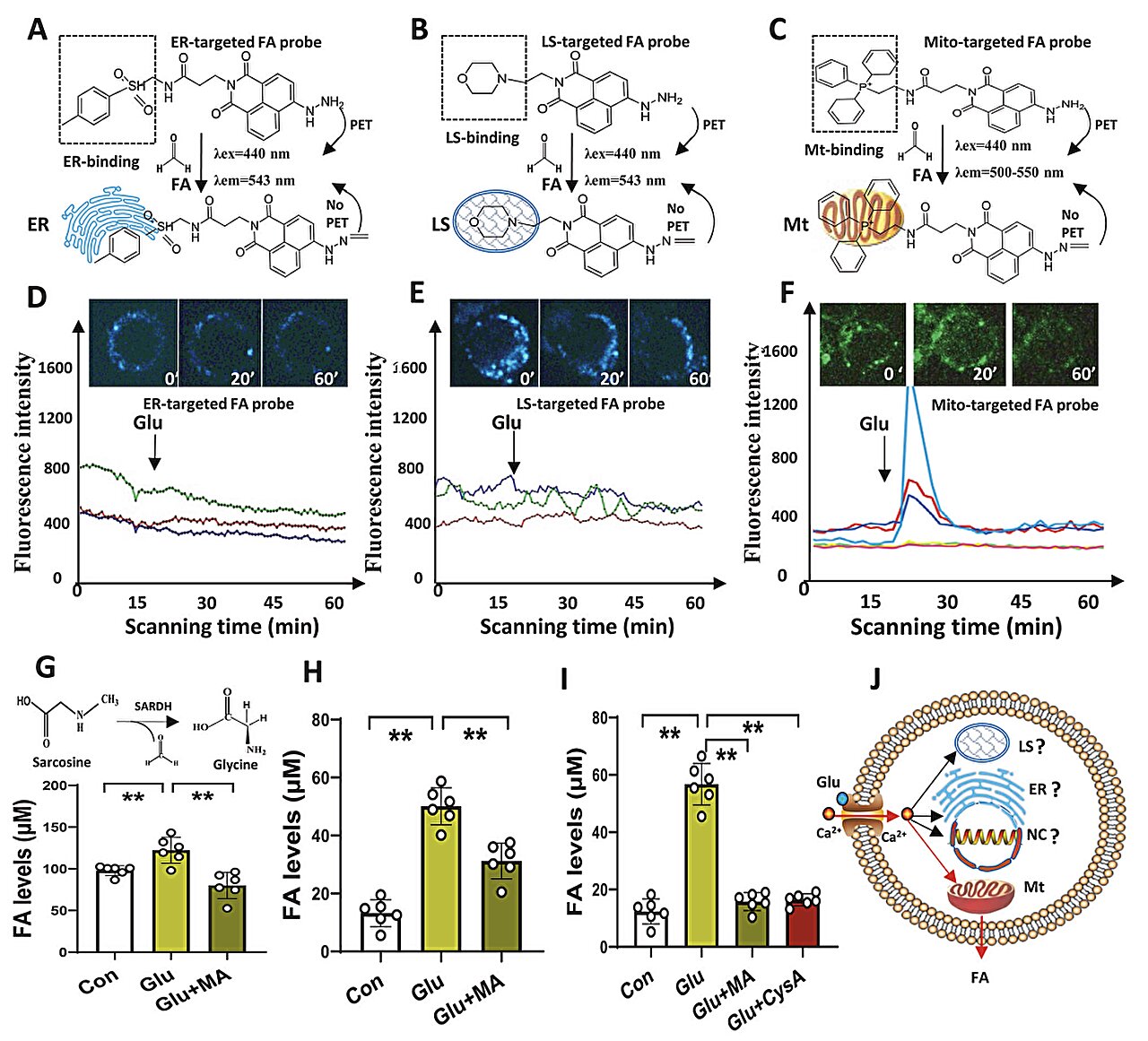

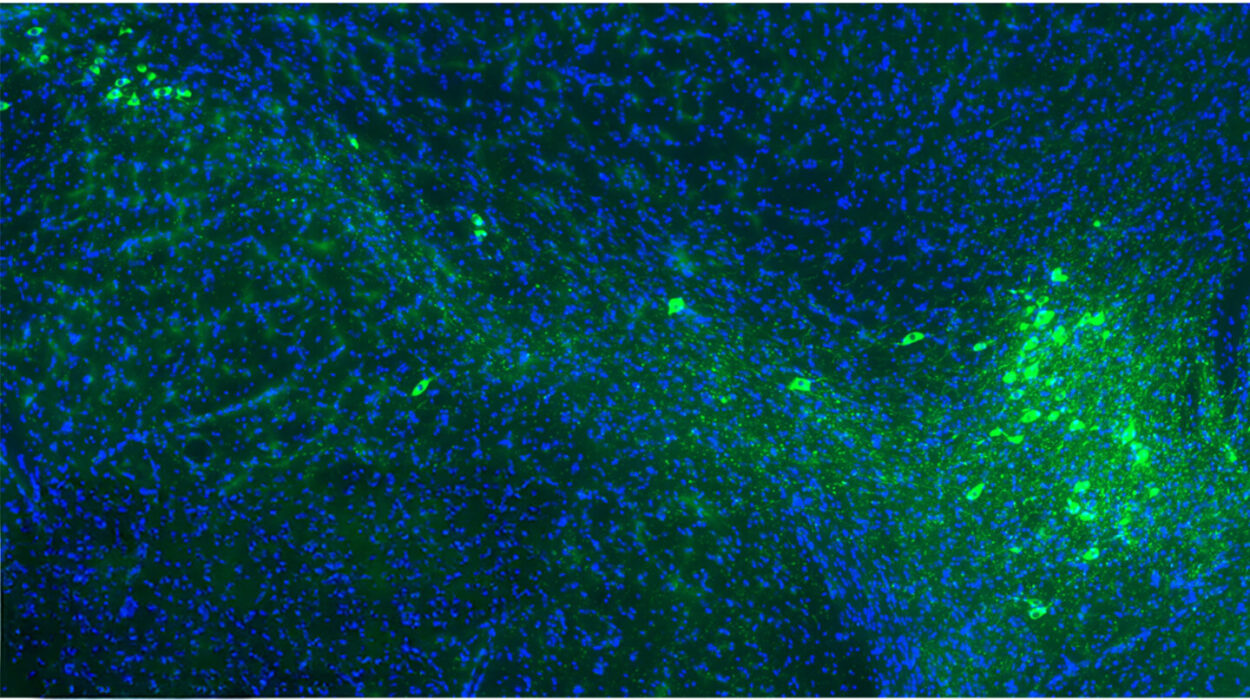

The team used highly sensitive chemical probes—specialized molecules designed to glow when they encounter their target—to track the movement of formaldehyde in real-time. What they found was a direct correlation between pressure and chemistry. When mice were subjected to chronic unpredictable mild stress, their hippocampal neurons began to churn out an excess of formaldehyde. This wasn’t just a side effect; it was a biological weapon.

The researchers utilized “patch clamp” technology to record the electrical discharges of the brain and mass spectrometry to analyze the chemical soup within. They found that as formaldehyde levels rose, the electrical activity in the hippocampus began to falter. The neurons were essentially being “muted” by the chemical buildup, leading to physical atrophy and a decline in the brain’s ability to fire the signals required for a healthy, balanced mood.

The Disappearing Chemicals of Joy

The damage, however, went far beyond structural changes. The brain relies on a delicate cocktail of monoamines—neurotransmitters that act as the messengers of well-being. These include serotonin, which governs mood and sleep; dopamine, the driver of motivation and reward; and melatonin, the conductor of our internal clocks. When these chemicals are abundant, we feel capable, rested, and motivated. When they vanish, the hallmark symptoms of depression—insomnia, loss of appetite, and a profound lack of motivation—take hold.

The study revealed a devastating interaction: the excess formaldehyde was effectively “deactivating” these precious monoamines. “Our results showed that in cellular and mouse models, glutamic acid and both acute and chronic stress triggered FA production in hippocampal CA1 neurons,” the authors explained. “Excessive FA induced depressive behaviors due to FA buildup and decreased serotonin, dopamine, and melatonin levels in the extracellular space. Especially, excessive FA deactivated these monoamines, damaged hippocampal CA1 structure, and reduced neuro-excitability.” By neutralizing the brain’s natural “feel-good” chemicals, the formaldehyde created a biological environment where joy was chemically impossible.

From Laboratory Models to Human Reality

To ensure these findings weren’t limited to animal models, the researchers expanded their scope to humans. They analyzed blood samples from patients and scrutinized magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of teenagers diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder. They also delved into the MENDA dataset, a massive public encyclopedia of chemicals found in the bodies of those struggling with anxiety and depression.

The patterns were unmistakable. The teenage patients showed the same hippocampal shrinking and monoamine deficiencies seen in the laboratory mice. Most tellingly, the level of formaldehyde in their blood acted as a biological barometer for their mental state. “Remarkably, adolescent MDD patients showed hippocampal CA1 atrophy and monoamine deficiencies, with blood FA levels predicting depression severity,” the researchers noted. The higher the formaldehyde, the more severe the depression.

A New Map for the Future of Mental Health

This research matters because it identifies a specific, measurable “trigger” for a disease that has long been treated with a one-size-fits-all approach. By proving that stress-derived formaldehyde is a critical driver of depression, this study provides a new target for the medical community.

These findings suggest that “stress-derived FA serves as a critical trigger of depression by inactivating monoamines and impairing hippocampal CA1.” Understanding this pathway opens the door for the development of entirely new diagnostic tools. Instead of relying solely on self-reported feelings, doctors might one day use formaldehyde levels to identify those at the highest risk for severe depression. Furthermore, it paves the way for treatments designed to limit the production of this chemical or protect the brain from its corrosive effects. By identifying the silent saboteur within, science has taken a vital step toward reclaiming the biological territory lost to depression, offering hope for more precise and effective ways to restore the brain’s natural balance.

Study Details

Yiqing Wu et al, Decoding depression: stress-derived formaldehyde initiates depressive symptoms in mouse and human, Molecular Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-025-03405-2